THE CASE TO END THE FED

Walking a Tightrope Amid a Waning Role—BTC Looms Large

Has the Fed era come to an end? This question is increasingly being asked by many—it is the elephant in the room. It’s also the message President Trump has apparently been signaling to the American people.

This article takes an in-depth look at the declining effectiveness of the Federal Reserve and questions about its viability moving forward.

Effectiveness and Evolution of Federal Reserve Monetary Policy

Introduction

The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) is tasked with a dual mandate: maintain price stability (low inflation) and maximum sustainable employment. Traditionally, the Fed’s primary tools to influence the economy have been adjustments to short-term interest rates and, in extraordinary times, large-scale asset purchases known as quantitative easing (QE). In recent years, however, these tools appear to have lost some of their punch. Inflation surged well above the Fed’s 2% target in 2021–2023 and remains stubbornly elevated, despite the Fed holding interest rates at their highest level in decades for over two years. At the same time, unemployment has stayed near historic lows – a puzzling outcome by past standards. This report examines two key premises:

Waning Efficacy of Traditional Tools: The Fed’s rapid and prolonged interest-rate hikes since 2022 have failed to fully tame inflation or loosen an unusually tight labor market. Structural factors – from supply-driven “structural” inflation to post-pandemic labor shortages, technological changes, and strongly anchored inflation expectations – have weakened the transmission of monetary policy. In effect, the usual link between Fed policy, inflation, and employment has become less predictable.

QE as a Fiscal Backstop: What began as an emergency measure (QE) to stabilize markets in 2008 and 2020 has evolved into a de-facto fiscal policy tool, enabling massive government deficits to be financed with newly created money. The Fed’s balance sheet expanded to unprecedented levels, purchasing trillions in U.S. Treasury debt. Critics argue this “debt monetization” bypasses Congressional spending limits and the debt ceiling, raising concerns about fiscal discipline. We analyze how sustained QE has financed federal deficits, whether there is sufficient real demand for the flood of Treasuries, and the potential consequences of the Fed’s continued intervention – including risks to U.S. financial credibility and the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

Throughout this report, we incorporate the latest data (2023–2025), quotes from Fed officials and economists, historical comparisons, and charts illustrating key trends – from inflation and employment to the Fed’s balance sheet and Treasury issuance. The tone is intentionally critical, probing the limits of the Fed’s influence and the dangers of blurring monetary and fiscal policy.

The Fed’s Dual Mandate and Traditional Policy Tools

Price Stability vs. Full Employment: Congress has directed the Fed to aim for low, stable inflation (around 2% annually) and maximum sustainable employment. Pre-2008, the Fed mainly used open-market operations to set the federal funds rate, which influenced borrowing costs economy-wide. By raising rates, the Fed could cool an overheating economy (and curb inflation); by cutting rates, it could stimulate borrowing, spending, and hiring. This conventional lever generally managed the post-Volcker era business cycles reasonably well – inflation stayed low (~2%) from the 1990s until 2020, and unemployment oscillated with economic booms and recessions in a relatively predictable manner.

However, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis pushed the Fed into uncharted territory. With rates at zero, the Fed launched QE – buying Treasury and mortgage-backed securities – to further stimulate growth. The result was a swelling Fed balance sheet (from under $1 trillion pre-2008 to about $4.5 trillion by 2015) and ultra-low long-term interest rates. Yet even as the economy recovered, inflation remained subdued (often below 2%), leading some to question if the Phillips Curve (the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment) had flattened. Indeed, research finds that better-anchored inflation expectations in recent decades have weakened the link between unemployment and inflation, flattening the Phillips curve. In practice, this meant the Fed could push unemployment lower without igniting inflation – a fortunate scenario through the 2010s. But the post-pandemic period turned that paradigm on its head, with inflation spiking for the first time in decades.

Post-2020 Challenges: The COVID-19 pandemic and the unprecedented fiscal and monetary response created a unique test for the Fed’s tools. Congress injected over $5 trillion in stimulus (over 20% of GDP) in 2020–21, much of it financed by Fed bond purchases. This, combined with supply chain breakdowns and pent-up consumer demand, led to a surge of inflation in 2021–2022 unseen since the early 1980s. The Fed was initially slow to pivot (relying on forecasts that proved too sanguine), but by March 2022 it began aggressive rate hikes. The federal funds rate rocketed from near 0% to over 5% in just a year – one of the fastest tightening cycles on record. The Fed hoped that such monetary tightening would brake demand and bring inflation back to target relatively quickly.

Premise 1: High Rates, Stubborn Inflation, and Labor Market Resilience

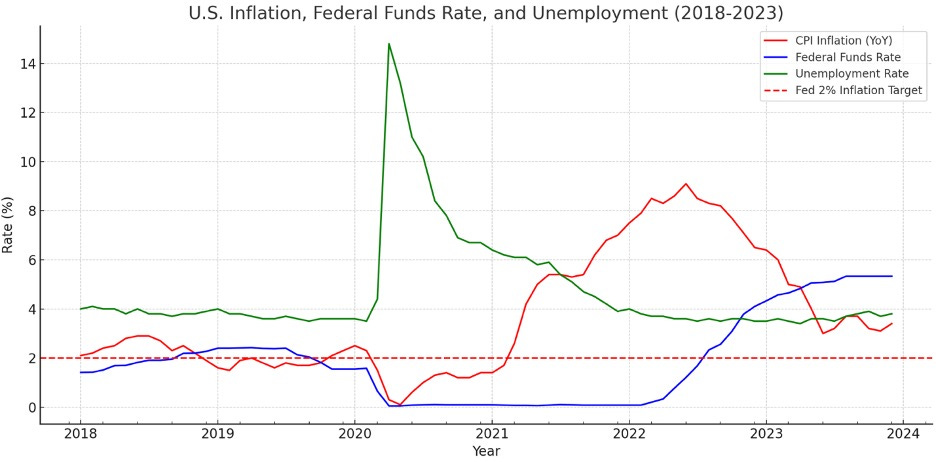

Figure: U.S. inflation (CPI, red line) versus the Fed’s interest rate (Fed Funds, blue line), 2018–2023. Inflation spiked to ~9% in 2022 – far above the Fed’s 2% goal (blue line) – and has declined but not yet returned to target. “Full Employment” at ~4% (green lie) has held steady since 2022. The Fed raised rates sharply to ~5% by 2023 and has maintained those high rates. Yet inflation remains “above the Committee’s 2 percent objective” and unemployment (green line, see next figure) stayed near historic lows.

Unprecedented Tightening vs. Persistently High Inflation

By early 2023, the Fed had raised its benchmark rate to the 5.25–5.50% range and held it there – the highest in over 15 years. Normally, such tight policy would be expected to cool consumer spending, business investment, and hiring, thereby easing price pressures. Indeed, inflation did moderate from its 2022 peak. Annual PCE inflation (the Fed’s preferred measure) peaked around 7.1% in June 2022 and then decelerated through 2023. However, progress stalled with inflation still “above the Fed’s 2% target at the end of 2023.” As of early 2025, inflation remains stuck in the 3–4% range – elevated and “too high” in the Fed’s own view. In April 2024, Fed officials fretted that half the items in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) were still rising >3% annually – inconsistent with returning to 2% inflation. Measures of underlying inflation even ticked up in early 2024 (core CPI accelerated from a 3.1% annualized pace to nearly 3.9% over six months), prompting some Fed members to warn that “the Fed is not done fighting inflation and rates will stay higher for longer.”

In essence, the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes have so far failed to fully “break the back” of inflation. Price pressures initially slowed when supply bottlenecks eased (e.g. goods and commodities inflation subsided in 2023), but a core of inflation proved sticky, notably in services. Fed Governor Michelle Bowman noted in 2024 that “inflation is still running above 2 percent and labor markets still [are] tight,” warranting a continued restrictive stance. The hoped-for quick victory – getting inflation back to 2% – did not materialize by 2024, despite interest rates at their highest since 2001. This raises the question: why has inflation remained above target when monetary medicine was applied so forcefully?

Structural Drivers of Inflation: Beyond the Fed’s Reach

A key part of the answer is that much of the recent inflation has been “structural” or supply-driven, rather than purely a result of excess demand. As one analyst put it, “The 2021–2023 burst of inflation was caused by bottlenecks and dislocations in the supply chain, about which the Fed can do nothing whatsoever.”

In other words, no amount of rate hikes can instantly produce more semiconductors, untangle ports, or pump more oil. During 2021–22, pandemic aftershocks led to shortages in everything from microchips to labor. Massive fiscal stimulus gave consumers spending power, but goods were in short supply – a recipe for price spikes. Concurrently, global events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 sent fuel and food prices soaring. These supply shocks fueled an inflation that the Fed’s demand-side tools could only partially offset. “Inflation...was widespread” across categories in 2021–22, noted a St. Louis Fed review, with food, energy, goods, and services all contributing to the surge. By 2023, goods inflation eased as supply chains normalized and energy prices even fell, but services inflation – largely driven by wage costs – remained “well above 2%.” This suggests a structural inflation component tied to labor market dynamics (e.g. a shortage of workers pushing up wages in service industries), which is not easily solved by interest rate hikes.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell explicitly acknowledged these limits. In late 2022, he remarked that “the biggest remaining barrier to taming inflation is the shortage of workers,” which was giving employees more clout to demand higher pay. He pointed out that higher-than-expected retirements, ongoing COVID-19 illnesses, and a drop in immigration have left the labor force smaller than it otherwise would be. “Policies to support labor supply are not the domain of the Fed: our tools work principally on demand,” Powell noted, underscoring that rate hikes can’t directly put sidelined workers back in jobs. In short, a structural labor shortfall has kept wage growth and price pressures elevated even as the Fed tightens policy.

Other structural forces may also be at play. Some economists highlight de-globalization and geopolitical shifts (e.g. reshoring of production, trade barriers) as putting upward pressure on costs. Demographics could be another factor – an aging population and slowing workforce growth tend to constrain the supply side of the economy. Additionally, energy transition policies (decarbonization) might introduce certain price pressures (at least during the transition) for fuel and power. While these trends are harder to quantify, they suggest that the inflation of the early 2020s is not a simple cyclical boom that the Fed can easily choke off; it has deeper roots that render the Fed’s task more complex.

Labor Market Constraints and Resilience

Perhaps the most striking development is the resilience of the labor market in the face of rapid monetary tightening. Historically, when the Fed raises rates aggressively, the economy cools and unemployment rises – often tipping into recession (e.g. early 1980s, early 1990s, 2008). This time, however, even after the Fed’s 500+ basis points of hikes, unemployment has barely budged. The U.S. jobless rate was 3.5% in early 2022 and still only 3.8% in early 2025, near a 54-year low. Job growth, after an initial post-pandemic boom, did slow in 2023, but then picked up again. By late 2023, the economy was adding a healthy number of jobs each month and “job growth [had] turned higher”, confounding expectations of a cooling economy.

Figure: U.S. unemployment rate (%). After spiking to ~14–15% during the April 2020 lockdown shock, unemployment plunged back to ~3.5% by early 2022 and has since fluctuated only slightly around historic lows. Even as the Fed raised rates sharply, the labor market remained exceptionally tight by historical standards.

The labor market’s tightness is evident in metrics like the job vacancies-to-unemployed ratio, which hit record highs in 2022. For much of 2022, there were roughly 2 job openings per unemployed person – an unprecedented situation. Companies struggling to hire often bid up wages to attract scarce workers. Powell noted in mid-2022, “we’re getting really nothing in labor supply now,” meaning the labor force wasn’t growing enough to alleviate the worker shortage. In this environment, the usual Fed strategy to cool wage growth is to reduce labor demand (i.e. induce job cuts and higher unemployment). Indeed, Fed officials have stated that unemployment may need to rise to around 4.5% (from ~3.5%) to rebalance supply and demand in the job market. Yet, achieving that without a recession has proven difficult. Through 2023, unemployment only ticked up to ~3.9% before easing back down. The feared wave of layoffs never materialized beyond isolated sectors like tech. Instead, businesses largely hoarded labor, perhaps due to lessons from the hiring difficulties post-COVID.

Several structural labor market factors underlie this resilience:

Labor Force Shrinkage: As Powell highlighted, millions of workers left the labor force during the pandemic (due to early retirements, health concerns, caregiving, immigration declines). As of mid-2022, labor force participation was still well below pre-pandemic levels. This means the effective labor supply is lower, making the job market tight even if labor demand is only moderate.

Post-Pandemic Labor Dynamics: The pandemic may have structurally changed work preferences and availability. For instance, some workers became more selective, seeking remote or flexible work (as illustrated anecdotally by workers like Dreanda Cordero, who rejoined the workforce only upon finding a suitable flexible job). The rapid rebound in labor demand, combined with these shifting preferences, created mismatches. Companies raised wages to fill positions (wage growth in 2022 was the fastest in decades).

Productivity and Reallocation: Interestingly, even with a smaller workforce, economic output recovered quickly, implying a burst of productivity. Some Fed officials in late 2024 began to consider that “the economy is shifting gears” with higher productivity allowing more output with less inflation. If firms are finding ways to produce more with fewer workers (perhaps via technology, automation, or efficiency gains), they can sustain growth without as much hiring – which might help explain why unemployment stayed low (few layoffs) even as output grew. Higher productivity could also, in theory, help reduce inflationary pressure (more supply). Indeed, U.S. productivity growth post-2019 averaged ~1.8% annually, higher than the ~1.5% of the prior decade, and showed signs of further acceleration. Some attribute this to the rapid adoption of digital tools and possibly early impacts of artificial intelligence. While promising, such gains also complicate the Fed’s estimates of economic potential, and the amount of tightening needed.

Household and Business Buffers: Another reason the labor market (and broader economy) weathered high rates could be that households and firms entered this period with unusually strong financial cushions. Trillions in federal aid during the pandemic left households with excess savings and businesses with cash buffers. Households also refinanced debt at record-low interest rates in 2020–21, locking in cheap 30-year mortgages and other loans. As a result, the typical choke points of Fed tightening – e.g. surging mortgage payments squeezing consumers, or high debt costs forcing firms to cut jobs – were muted. Most homeowners saw no change in their mortgage due to fixed rates, and many corporations termed out debt at low rates, delaying the impact of higher yields. This reduced the transmission of rate hikes to spending. The housing market did cool for new buyers, but existing homeowners (the majority) weren’t directly hit with higher monthly payments. Consumer spending thus held up longer than expected, keeping demand for workers robust. By late 2023, consumer spending was still “supported by solid increases in income”, helping GDP growth stay positive. In short, the usual demand slowdown that rate hikes induce has been less severe, so far, than historical precedent – explaining why unemployment hasn’t risen much.

Weakened Monetary Transmission Mechanism

The phenomena described above point to a weakened monetary policy transmission in the current environment. The Fed’s rate hikes have certainly affected parts of the economy – for example, home sales and refinancings plummeted with 7%+ mortgage rates, and interest-sensitive sectors like tech saw stock corrections and some layoffs. But broadly, the impact of higher rates has been unexpectedly modest on aggregate demand. Fed officials themselves have been surprised by the economy’s momentum. As of December 2023, the Fed noted that the economy “continued to grow above trend” and that a feared slump had not materialized. Instead of a classic recession, the U.S. experienced a sort of mini-boom by late 2023: GDP growth rebounded, and consumer confidence rose, even as borrowing costs were at decade highs.

Several technical factors in the financial system help explain this. The Fed’s massive QE in prior years left banks awash in reserves and liquidity. Unlike in past tightening cycles, banks in 2022–2023 did not face funding scarcity; in fact, the Fed paid banks interest on their excess reserves (now at the high Fed rate). This meant the banking system as a whole wasn’t forced to contract credit as sharply – banks could maintain lending using their liquidity stockpiles or by paying higher deposit rates rather than simply calling in loans. Credit did tighten somewhat (especially after some bank stresses in March 2023), but it was not a collapse. Additionally, the global demand for dollar assets remained strong – U.S. Treasury yields, while higher, stayed in a range that didn’t cripple government or private borrowing. Some commentators have argued that with inflation expectations well-anchored, the real interest rates (inflation-adjusted) were not extremely high, so policy, while restrictive, was not brutally so. Households and firms might also have treated the inflation surge as temporary (given the Fed’s credible commitment to 2%) and thus did not drastically cut spending; many could dip into savings or take jobs in a hot labor market to cope with higher prices in the interim.

Anchored inflation expectations in particular are a double-edged sword. On one hand, well-anchored expectations are a testament to the Fed’s credibility – people believe the Fed will eventually get inflation back to ~2%, so long-run inflation expectations have remained near 2%. This helps prevent a wage-price spiral; workers and firms expect only moderate future inflation, so they do not behave as if high inflation will persist indefinitely. Indeed, research finds that when expectations are firmly anchored, the Phillips Curve flattens because temporary rises in inflation don’t feed into higher expected inflation. This likely prevented the 2021–2022 inflation from escalating even further – an important success for the Fed’s credibility. On the other hand, anchored expectations might make short-run inflation less responsive to slack. If everyone assumes inflation will go back down, firms might be slower to cut prices and workers less inclined to accept wage restraint, even if the economy cools a bit. In effect, the Fed may need to exert more pressure (i.e. keep rates higher for longer) to convince everyone that inflation is truly returning to target. This is a topic of active debate. Some Fed researchers argue that improved anchoring “shrinks” the apparent responsiveness of inflation to economic slack. The risk, however, is if the Fed fails to bring inflation down reasonably soon, even anchored expectations could become unanchored – a dangerous scenario that would greatly amplify the Fed’s challenges.

In summary, Premise 1 holds: The Fed’s traditional interest rate lever is proving less potent in the current cycle. High inflation has not yielded easily to higher rates, and low unemployment has defied the usual trade-off. Structural inflation forces, labor shortages, and muted policy transmission have all undercut the Fed’s influence. As Fed Chair Powell conceded, achieving a soft landing with inflation down to 2% “has a long way to go,” and it will require some luck with supply-side improvements since “our tools work on demand, not supply.” The experience of 2022–2024 may prompt a reevaluation of how the Fed conducts policy in a world where the old assumptions (e.g. a 4% unemployment necessarily causes inflation, or a sharp rate hike necessarily causes a recession) no longer strictly hold.

Premise 2: Quantitative Easing – From Emergency Tool to Fiscal Backstop

While the Fed has struggled to rein in inflation with traditional means, it has simultaneously been engaged in (or recently emerged from) an extraordinary experiment in money creation and bond buying. Quantitative Easing (QE), once considered a radical response to the 2008 crisis, became almost routine by the 2020 pandemic. Through QE, the Fed buys assets (mainly U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities) in large quantities, injecting liquidity into the financial system. Initially justified as a way to lower long-term interest rates and support credit flows when short-term rates hit zero, QE has had the side effect of financing government deficits on a massive scale. This section analyzes how QE evolved into a “fiscal backdoor” – effectively allowing the government to spend far beyond its revenues, with the Fed creating money to cover the gap. We’ll explore the mechanics and scale of this phenomenon, and why it raises concerns about sustainability, Fed independence, and future inflation/credibility risks.

QE’s Massive Expansion of the Fed’s Balance Sheet

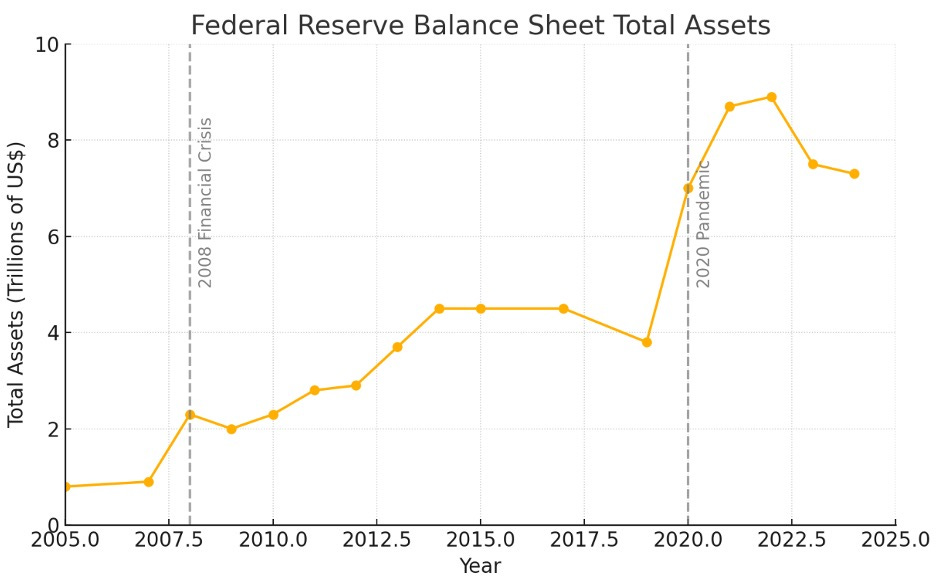

To appreciate the scale of QE, consider the Fed’s balance sheet (the sum of assets it holds, mostly government bonds). Before 2008, the Fed held under $1 trillion in assets, accumulated slowly over decades. Today, that figure is around $7–8 trillion. The chart below illustrates how unprecedented this expansion is:

Figure: Federal Reserve Balance Sheet (Total Assets). The Fed’s assets exploded from under $1 trillion in 2007 to ~$8–9 trillion at the peak of QE in 2021–2022. Major surges correspond to QE programs during the 2008–2009 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. Even after starting balance sheet reduction (QT) in late 2022, the Fed’s holdings in 2024 remain an order of magnitude larger than pre-2008.

During the 2008 crisis, the Fed launched QE1, QE2, and QE3 in successive waves, buying Treasury and agency mortgage bonds to stabilize the financial system. By 2014, its balance sheet reached about $4.5 trillion (vs ~$0.9T in 2007). This was double the prior trend, but the Fed at that time maintained that QE was a temporary emergency measure. Indeed, from 2017–2019, the Fed engaged in modest quantitative tightening (QT), reducing its assets to about $3.8 trillion.

However, when the pandemic hit in March 2020, the Fed responded with “QE on steroids.” In a matter of weeks, the Fed announced it would buy Treasury and MBS “in the amounts needed” to restore market functioning – essentially an unlimited QE commitment. The Fed’s holdings shot up by ~$1 trillion in just Q1 2020 as it backstopped a Treasury market in turmoil. Over the next two years, the Fed kept purchasing at a rate of $80 billion in Treasuries and $40 billion in MBS per month. By early 2022, the balance sheet hit $8.9 trillion. As the Parametric Portfolio analysis notes, the Fed “doubled the size of its balance sheet during the pandemic,” accumulating over $5 trillion in Treasuries at the peak in 2022. This was a direct response to the federal government’s extraordinary borrowing needs in 2020–21.

Crucially, QE meant the Fed was absorbing a huge share of new Treasury issuance. In fact, studies show that between March 2020 and January 2021, the Fed bought roughly 47% of all Treasuries issued in that period. Essentially, the Fed was creating money to lend to the Treasury (albeit indirectly via secondary markets). This blurs the line between monetary and fiscal policy. Normally, the government would fund deficits by selling bonds to private investors, who have finite appetite and will demand higher yields if debt supply soars. But with the Fed stepping in as a buyer of last resort, trillions in debt were sold without pushing yields up commensurately. The result: the government’s massive pandemic deficits were financed at extremely low interest rates, with little immediate pressure from markets or Congress to constrain spending.

By using QE in this way, the Fed effectively enabled the government to bypass traditional fiscal restraints. In 2020, Congress and the Treasury did face a statutory debt ceiling, but that ceiling was repeatedly raised, and given the emergency, there was bipartisan agreement to spend what was necessary. The Fed’s actions made that spending far easier: it soaked up debt supply and rebated much of the interest back to Treasury (since Fed profits go back to the government). Some have described this as “fiscal dominance” – a regime where the central bank prioritizes financing the government over its inflation mandate. While the Fed did not overtly say it was financing deficits (it framed QE as market stabilization and monetary stimulus), the outcome was that the federal government’s deficits were monetized on a vast scale.

QE as a Backdoor for Government Spending

Economists from the Hoover Institution observed that the Fed’s models underestimated the inflationary impact of the huge fiscal stimulus in part because they failed to account for the “historical link between budget deficits accommodated by easy monetary policy and inflation.” In other words, when central banks print money to finance deficits, inflation tends to follow – a lesson from many countries’ histories (though the U.S. hadn’t experienced it in a long time). By 2021–2022, that link manifested as inflation surged, suggesting that the QE-funded deficit spending did contribute to overheating.

Critics argue that QE has become a “fiscal policy substitute”. Cato Institute’s George Selgin warns of “The Menace of Fiscal QE,” noting that thanks to changes in the Fed’s operating framework, it now has “practically unlimited powers of QE: it can buy as many assets as it likes while still controlling inflation” via interest on reserves. This removes the natural constraint on money-printing; in the past, creating too much money would automatically lead to inflation, but now the Fed can, in theory, pay banks to hold excess money (to prevent an immediate inflation spike) while continuing to fund government spending. Selgin cautions that some politicians see this as a tempting tool to finance large programs “without democratic control of spending,” effectively using the Fed’s balance sheet instead of raising taxes or borrowing from the public. If the Fed were forced (by political pressure) to use QE purely to accommodate federal deficits – “backdoor spending,” as he calls it – that would threaten the Fed’s independence and blur accountability for economic outcomes.

The evidence from the pandemic period supports the view that QE enabled “unchecked” spending in the sense that normal fiscal hurdles were minimal. Trillions were spent very quickly; the usual worry of “who will buy all this new debt?” was allayed by the Fed’s presence. Moreover, the debt ceiling was effectively neutralized as a binding constraint during that time – Congress raised it pro forma, and the Fed’s actions ensured that markets could absorb the new issuance without drama. In essence, the Fed became a major financier of the U.S. government. By mid-2022, the Fed held roughly $5.8 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities (and additional trillions of MBS)– making it the single largest holder of U.S. government debt, ahead of even the Social Security Trust Fund or foreign nations.

To put this in context, the Fed’s Treasury holdings around 2007 were only about $0.8 trillion. So, in 15 years, the Fed’s share of U.S. debt went from negligible to dominant. The Federal Reserve’s portfolio by 2022 included a large portion of all marketable Treasury bonds – meaning a significant part of the national debt was essentially owed to another arm of the government (the central bank) rather than to external creditors. The consolidation of fiscal and monetary operations is evident here: from a consolidated government perspective, when the Fed holds Treasuries, the government owes money to itself (since the Fed returns profits). An IMF analysis noted that QE can lower the net public debt because the central bank holding debt is not the same as a foreign investor holding it. This makes it alluring to policymakers – it’s as if debt and deficits don’t matter as much because the central bank can absorb them.

Sustainability of Soaring Deficits and Limited Buyers

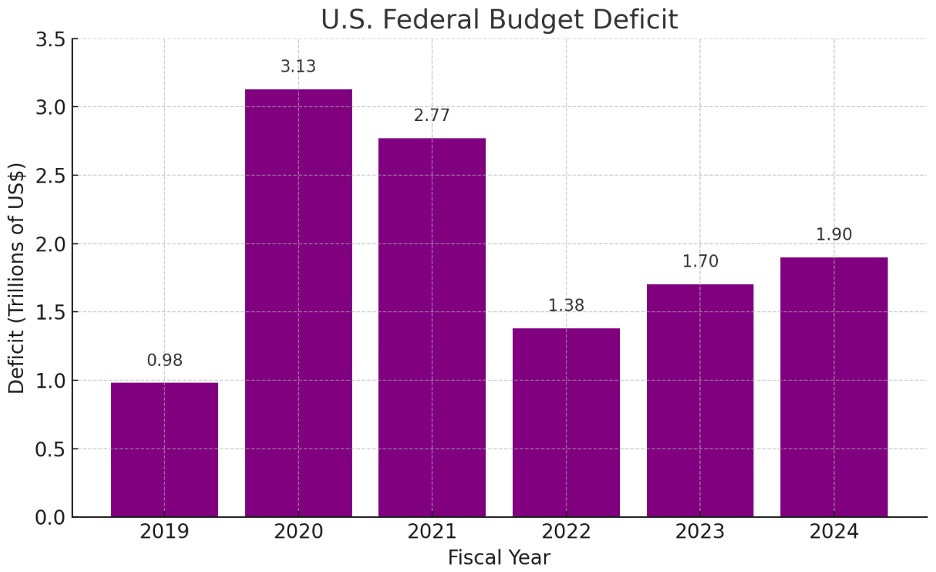

The U.S. ran enormous budget deficits in recent years: $3.1 trillion in FY2020, $2.8 trillion in 2021, and still $1.7 trillion in 2023. While the deficits shrank from the COVID peak, they remain very high by historical standards – around 7% of GDP in 2023, more than double the ~3% 50-year average. The chart below shows the recent trajectory of federal deficits:

Figure: U.S. Federal Budget Deficits (FY2019–2024). The pandemic drove deficits to record levels (~$3T in 2020), and although they receded, 2022–2024 deficits (~$1.4–$1.9T/year) are still far above pre-pandemic norms. In FY2024 the deficit is projected about $1.9 trillion. These persistent shortfalls imply heavy Treasury issuance that must be financed by investors or the Fed.

A critical question is: Who will buy all these Treasuries if the Fed steps back? In 2022, the Fed stopped net new purchases and even began allowing bonds to run off its balance sheet (QT). This meant the private market had to absorb larger volumes of Treasury issuance. Initially, this caused turbulence – by late 2022 and 2023, longer-term Treasury yields had risen sharply (the 10-year note yield hit around 4.5%, up from ~1% in 2020). The Stanford Institute (SIEPR) study by Lustig et al. found that “the U.S. is issuing a lot of Treasury debt, and investors are not as excited as they used to be about absorbing all of it.” They observed that whenever the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) announced large new debt projections, Treasury yields spiked – a sign that markets were demanding a price (higher yield) for the flood of debt. In spring 2020, a “flight from maturity” occurred: sophisticated investors sold off long-term Treasuries, anticipating that the massive deficits would eventually drive prices down (yields up). In fact, from 2020 to 2023, the market value of outstanding Treasuries fell ~26% – one of the biggest bond bear markets in U.S. history.

Foreign buyers, historically major holders of U.S. debt, have also been less avid. Countries like China and Japan scaled back net purchases. Foreign official holdings of Treasuries actually declined in late 2020 as central banks globally reduced exposure. This left domestic investors (banks, funds, households) to pick up more slack. But domestic balance sheets have limits too. By mid-2023, concerns grew that without the Fed, the sheer volume of new Treasury issuance (to fund ongoing 6-7% GDP deficits) would overwhelm demand. Apollo Global Management estimated roughly $10 trillion of Treasuries would hit the market from 2024–2025 when accounting for new borrowing and rollovers– a staggering sum for private markets to absorb in a short time.

The Parametric Portfolio analysis put it succinctly: “Elevated budget deficits imply growing US Treasury issuance. Receding demand from central banks could leave more price-sensitive buyers to pick up the slack.” Those price-sensitive buyers will require higher yields (lower bond prices) to be enticed. Indeed, in 2023 we saw the 30-year mortgage rate climb near 8% and Treasury yields approach multi-decade highs, reflecting this adjustment. Higher government bond yields, in turn, raise the cost of borrowing for the Treasury, creating a vicious cycle for debt sustainability. The Congressional Budget Office warns that U.S. interest costs on debt will soar: net interest outlays are projected to exceed defense spending by 2024. The U.S. will be spending more on servicing past debts than on investing in its military or other priorities – an unsustainable trajectory if deficits aren’t curbed.

If such pressures intensify, the Fed could again face a dilemma: allow market forces to push yields up sharply (which could destabilize markets and hurt the economy) or intervene with renewed bond-buying (QE) to cap yields and ensure the Treasury can finance itself. The latter path, however, would confirm the “fiscal dominance” regime – the Fed essentially underwriting government borrowing needs. This is reminiscent of post-World War II policy (the Fed pegged yields to help government debt management) and is the opposite of the Fed’s independent inflation-targeting stance since 1980. Fed officials today remain publicly committed to fighting inflation, not explicitly financing deficits. Indeed, in 2023–2024 they continued QT, shrinking the balance sheet by about $500 billion. But if financial stress or recession hits, there is an expectation in markets that the Fed would pivot back to easing (including QE if needed). The risk is that each new round of QE makes the Fed more entangled with fiscal matters.

Consequences: Financial Credibility and the Dollar

The evolution of QE into a fiscal backstop carries several potential consequences:

Inflation and Loss of Control: Monetizing debt is inherently inflationary if done to excess. So far, the Fed managed to prevent QE from causing runaway inflation by later reversing course (raising rates, doing QT) once the economy recovered. But if the Fed were compelled to keep buying debt to fund persistent deficits, it might not be able to withdraw support without causing a fiscal crisis. This could lead to a scenario of fiscal dominance, where the Fed has to tolerate higher inflation rather than undermine Treasury financing. Investors might start expecting higher inflation in the long run, un-anchoring expectations and leading to a self-fulfilling rise in prices. The “fiscal theory of the price level” basically states that if fiscal solvency is in doubt, inflation will adjust to erode the real value of debt. The U.S. is not near an insolvency point, but the credibility of its anti-inflation commitment could be questioned if money printing becomes a habitual solution. As one commentator put it, “Americans still haven’t digested that the bond market was sending a message during COVID: if deficits remain huge with no plan to offset them, Treasuries can become a risky investment”

Threat to Reserve Currency Status: The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency is underpinned by trust in U.S. financial stability and rule of law, and deep, liquid Treasury markets. If QE-as-fiscal-policy were to erode that trust – say, by causing high inflation or perceptions of debt monetization – foreign investors might diversify away from dollar assets. Already, there are murmurs of some countries exploring alternative reserve assets (e.g. gold or other currencies) due to concerns about U.S. debt. To be clear, the dollar is in no immediate danger of losing reserve status; it still accounts for ~60% of global FX reserves and the U.S. Treasury market is unmatched in size. However, profligate fiscal policy financed by central bank money has led other nations into currency crises historically. The U.S. is unique in that its debt is in its own currency and widely held, but that advantage could be abused. Credit rating agencies have taken notice – in 2023, Fitch Ratings downgraded U.S. government debt one notch, citing “erosion of governance” and high debt trajectory. While largely symbolic, it underscores how the world is watching U.S. fiscal-monetary interactions nervously.

Fed’s Reputation and Independence: The more the Fed is seen as financing the government, the more its political capital may be at risk. Already, during the 2020–2021 QE, some elected officials openly urged the Fed to keep conditions easy to enable big spending packages. If the public comes to view the Fed as complicit in fiscal excess (especially if inflation stays above target), the Fed could face a loss of credibility. This might manifest in calls to change the Fed’s mandate or authority. Conversely, if the Fed resists aiding the Treasury and insists on prioritizing inflation, it could face political heat for allowing borrowing costs to rise (which could cause budget pain or even a default risk if Congress fights over the debt ceiling). This tug-of-war is precisely what Fed independence is meant to avoid – the central bank should not be hostage to short-term political/fiscal considerations. But with QE becoming common, the line has blurred. Former Fed officials have warned of a “slippery slope” where, in a future downturn, there will be pressure on the Fed to buy not just Treasuries but perhaps corporate bonds or other assets to prop up sectors (as happened briefly in 2020). Such quasi-fiscal actions, if repeated, could make the Fed a general financier of economic activity, diluting its focus on price stability.

Financial Market Distortions: Years of QE and low rates have arguably led to asset price distortions – extremely low yields encouraged risk-taking and high valuations. Reversing QE could similarly roil markets (2022’s bond market volatility is a case in point). If markets come to expect that the Fed will always step in (“Fed put”), they may not discipline fiscal policy until very late in the game. That could mean a more abrupt adjustment down the line. The Treasury market’s liquidity is also a concern; with the Fed so heavily involved, true market depth might be less than it appears. In 2020, when the Fed briefly stepped away (in March before announcing QE), the Treasury market saw a liquidity crisis. Reforms are being discussed to improve market resilience, but if the Fed keeps acting as a backstop buyer, it might actually discourage private market-making.

In summary, QE has indeed drifted into the realm of fiscal policy. It has allowed the government to run deficits of a magnitude and speed that would have been hard to finance under normal market conditions. While this helped avert economic catastrophe in 2020, it has set a precedent. The sustainability of this approach is questionable. The U.S. cannot monetize debt indefinitely without consequence – either inflation will eventually result, or the dollar will weaken, or political backlash will ensue (possibly all of the above). Already, researchers note the U.S. is exhibiting signs of a “risky debt regime” where investors demand higher yields due to expectations that future fiscal tightening (raising taxes or cutting spending) won’t happen. If those expectations worsen, the government could face a debt spiral that even the Fed cannot easily fix. The safest course to avoid such an outcome, as many economists suggest, is to restore fiscal discipline – i.e. reduce deficits to more normal levels – so that the Fed is not put in a position of having to choose between financing the Treasury or fighting inflation.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve’s experience in the mid-2020s reveals a central bank walking a tightrope between its twin objectives and new responsibilities thrust upon it.

Premise #1 highlights that the Fed’s traditional toolkit – primarily interest rate adjustments – is facing headwinds from structural economic changes. Inflation proved higher and stickier due to supply shocks and labor constraints that interest rate moves alone could not remedy. Yet, despite the highest rates in decades, the economy and job market showed uncanny strength, suggesting the transmission of policy has changed. This calls for humility and perhaps new thinking in monetary policy; the Fed may need to incorporate more supply-side analysis and be prepared for a flatter Phillips Curve when crafting policy. It also underscores the importance of non-monetary measures (fiscal policy, labor market policies, etc.) to address inflation’s root causes (for example, encouraging labor force participation or easing supply bottlenecks).

Premise #2 shines light on the Fed’s expanded role as the financer of last resort for the U.S. government. QE has blurred the boundary between fiscal and monetary realms, enabling massive deficit spending with minimal short-term pain. While this provided crucial support during crises, it raises the specter of longer-term pain: inflationary pressures, loss of Fed independence, and a pile of debt that grows ever larger. The U.S. is fortunate that the dollar is the world’s reserve currency – this gives it leeway that other countries lack. But even the U.S. has limits, and there is a growing chorus of warnings (from think tanks like Cato, to economists, to even Fed officials in more candid moments) that current fiscal trends are unsustainable. The Fed cannot indefinitely be the buyer of first resort for Treasury debt without eroding confidence in the currency.

In a sense, the Fed is caught in a feedback loop of its own making: QE helped fuel inflation (alongside fiscal stimulus), which the Fed then had to combat with rate hikes; those rate hikes make financing the debt more costly, which could tempt more reliance on QE to suppress rates. Breaking this loop will require careful navigation and likely some coordination between monetary and fiscal authorities – not in the sense of the Fed capitulating to finance deficits, but rather Congress taking fiscal responsibility so as not to corner the Fed. The late 1940s and early 1950s offer a historical parallel: after WWII, the Fed had kept yields low for the Treasury, but in 1951 the Treasury-Fed Accord freed the Fed to prioritize inflation stability, and fiscal policy was adjusted to gradually reduce the wartime debt burden relative to GDP. A modern accord might be needed: an understanding that fiscal policy will aim for sustainability, allowing the Fed to focus squarely on price stability without feeling compelled to monetize debt.

In conclusion, the Fed’s recent trials illustrate both the limits of monetary policy and the risks of overextending it. Traditional rate policy is not a cure-all, especially for supply-driven inflation, and QE – while powerful – is not a free lunch for the economy. The dual mandate is growing harder to achieve in a world of structural shifts and fiscal excess. Going forward, the Fed will need to communicate even more clearly and stick to its principles to keep inflation expectations anchored, and lawmakers will need to shoulder more of the burden in maintaining economic stability (through prudent fiscal management and policies to enhance the supply side of the economy). The credibility of U.S. financial leadership – and the dollar – will depend on getting this balance right. As Hemingway might analogize for excessive debt, problems can brew “gradually, then suddenly”– the time to reinforce the foundations is before the cracks turn into a crisis.

U.S. Repo Market Dynamics (2019–2025) and the Fed’s Evolving Role

Repo Market Evolution and Fed Influence (2019–2025)

The 2019 Repo Rate Spike and Fed Intervention: In mid-September 2019, U.S. overnight repo rates experienced a sudden, unprecedented spike. The secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) jumped from about 2.4% on Sept. 16 to over 5% on Sept. 17 (even hitting 10% intraday), while the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) briefly pierced above the Fed’s target range. This dislocation was traced to a temporary cash shortage: quarterly corporate tax payments and settlement of new Treasury issuance on Sept. 16 pulled roughly $120 billion in reserves out of banks, just as primary dealers had to finance a wave of Treasuries in repo markets. With “more Treasury securities to be financed…with relatively less cash,” repo demand outstripped supply. The rate spike was striking because it occurred after years of stable rates – a clear sign that bank reserves had fallen to the lower bound of “ample” levels due to Fed balance sheet runoff (QT) and rising Treasury debt.

Faced with this liquidity crunch, the Fed leapt into action. Starting September 17, 2019, the New York Fed conducted large overnight repo operations, injecting $75 billion that day and repeating as needed for weeks. The Fed also cut the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER) by 5 bps to coax the EFFR back into range. These moves quickly calmed markets; by September 20, overnight rates normalized. Notably, the Fed’s interventions didn’t stop there – the Fed began regular repo market liquidity provision through early 2020 and eventually resumed permanent asset purchases (of T-bills) in October 2019 to rebuild a cushion of bank reserves. In effect, the 2019 episode forced the Fed to abort its prior QT program and expand the balance sheet again. This marked a turning point in how the Fed managed short-term rates: it became clear that an “ample reserves” regime required careful calibration, and that the Fed might need new tools to prevent such funding stresses from recurring.

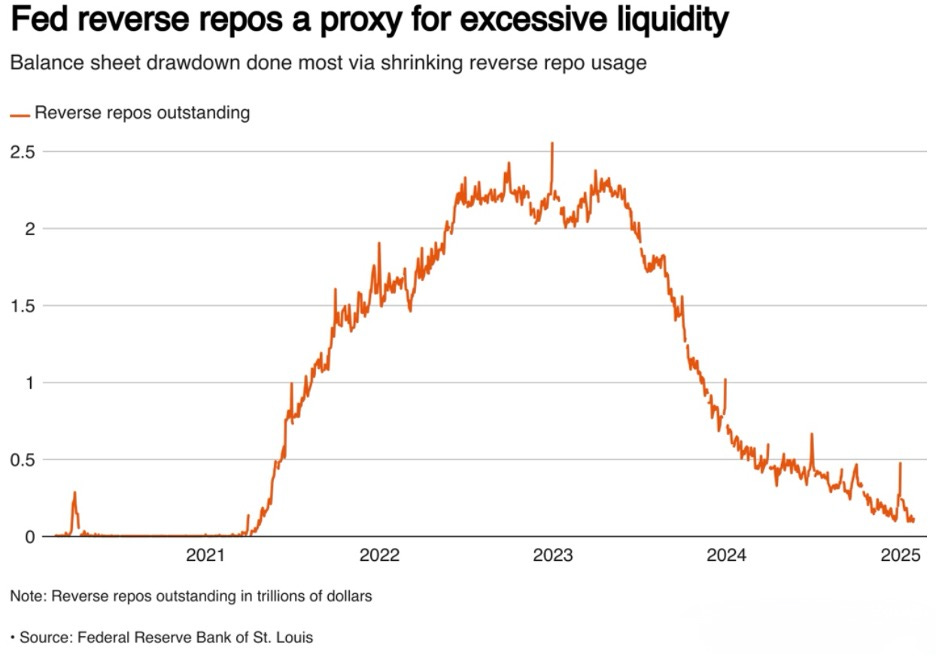

Rise of the Reverse Repo Facility (ON RRP): After 2019, the Fed enhanced its toolkit, notably by amplifying use of the overnight reverse repurchase agreement (ON RRP) facility. The ON RRP is effectively a cash-draining tool: the Fed borrows cash overnight from money-market players like money market funds (MMFs) and gives them Treasuries as collateral, paying a set interest rate. This facility, which had existed in testing, took on outsized importance after the 2020 COVID crisis. The Fed’s massive QE in 2020–2021 and the Treasury’s fiscal response flooded the system with liquidity, pushing short-term interest rates downward. By early 2021, banks were saturated with deposits and, due to regulatory leverage constraints, became less willing to absorb more cash. Consequently, excess cash flowed into government MMFs, which needed safe short-term outlets. At the same time, Treasury significantly reduced T-bill issuance in 2021 (shifting to longer debt), creating a scarcity of short-duration assets. The Fed responded by making its ON RRP more attractive – expanding counterparties and raising the offering rate. This combination of factors led to an extraordinary surge in ON RRP usage starting mid-2021.

By the end of 2022, the Fed’s ON RRP facility was absorbing over $2.5 trillion in excess liquidity daily. This was an all-time high, rising from essentially zero in early 2021 to $1+ trillion by late 2021 and peaking at ~$2.55 T in December 2022. MMFs parked cash at the Fed en masse – by late 2022, over 60% of MMF assets were invested in ON RRPs. The Fed thus became the counterparty of choice for much of the money-market, effectively intermediating between cash-rich funds and the Treasury securities market. This huge footprint reflects how financial institutions preferred the Fed’s risk-free facility over private lending during that period. While this ON RRP uptake allowed the Fed to maintain a floor under overnight rates (it offered ~4.3% in late 2022, helping keep fed funds near 4.33% within target), it also meant the Fed was doing “money-market maker” duty rather than letting private repo markets set rates. Observers noted that this “unhealthy development” could marginalize private markets and dull their price signals. In short, the Fed’s reverse repo facility became a double-edged sword: crucial for absorbing “excess liquidity that financial participants do not want” (as Fed Governor Chris Waller put it), but at the cost of entrenching the Fed at the center of money-market lending.

Reverse repos outstanding at the Fed (in trillions of USD). The facility ballooned from near-zero in 2020 to a ~$2.5 T peak, then began shrinking during 2023–2024. It has acted as a proxy for excess liquidity in the system.

QT (2022–2025) and Effects on Repo Markets: In early 2022, with inflation soaring, the Fed pivoted to quantitative tightening (QT) again – letting assets roll off to shrink its balance sheet. Crucially, the existence of the ON RRP “buffer” allowed the initial phase of QT to mainly drain excess cash rather than reserves needed by banks. Indeed, from mid-2022 through 2023, the bulk of Fed balance sheet reduction was mirrored by a drop in ON RRP balances (as MMFs pulled cash out to buy newly issued Treasuries and other assets). A surge in Treasury T-bill issuance after the mid-2023 debt ceiling resolution accelerated this drawdown: roughly $1.0–1.5 T flowed out of the Fed’s ON RRP as the Treasury General Account was refilled and T-bill supply normalized. By late 2024, reverse repo usage had fallen to around $0.5 T, and by early 2025 it dwindled to under $100 B. In fact, by Feb 2025 the facility stood at just ~$78 B – a 97% collapse from its peak. This rapid decline indicates that most of the pandemic-era excess liquidity has finally been soaked up. Fed officials have welcomed this trend: they long signaled a desire to shrink ON RRP “back to negligible levels,” seeing its runoff as a sign that true excess cash is gone, and that further QT will start reducing bank reserves. In other words, the ON RRP acted as a buffer reservoir during QT; only once it’s largely exhausted will QT actively press on banks’ reserve holdings, which is the point at which QT may need to stop. Estimates as of late 2024 suggested the Fed might halt QT around mid-2025, when the balance sheet reaches about $6.4 T, to avoid depleting reserves too far.

Notably, the Fed has been contemplating technical tweaks to encourage the remaining cash to leave the ON RRP. In December 2024, for example, many expected the Fed to cut the ON RRP rate by more than its policy rate cut – essentially lowering the “floor” return on parked cash to push MMFs into private markets. The logic was that as long as RRP offered relatively attractive, risk-free interest, some funds would stay “sticky.” By nudging that rate down to the bottom of the fed funds range, the Fed hoped to “encourage people to find alternatives” to parking money at the Fed. This underscores how managing the exit of excess liquidity has become an active policy task. Even so, analysts caution that a “sticky” base of cash may remain in ON RRP because certain large MMFs rely on the Fed’s facility for its ease and capacity, especially for late-day flows. Completely unwinding the Fed’s money-market footprint may not be trivial.

Is Reverse Repo Still a Barometer of Liquidity? Over this period, the ON RRP facility has proven to be a pretty clear gauge of system liquidity. When ON RRP usage was climbing to record highs, it signaled an abundance of cash with nowhere else to go – “excess liquidity” in the truest sense. Conversely, the steep fall in ON RRP balances in 2023–24 signals that liquidity is being absorbed back into the market (via T-bills, loans, etc.) and that the “excess” is finally being drained. In fact, the Fed and market observers explicitly view the level of ON RRP as an indicator of whether reserves remain ample. Fed officials noted that to avoid destabilizing reserve scarcity, they would likely end QT once the RRP facility is near zero. Thus, as a leading indicator, declining reverse repo usage has telegraphed tightening liquidity conditions. That said, the ON RRP is also influenced by technical factors (like the Treasury’s debt management). For example, its sharp drop in 2023 was in large part a one-off response to Treasury filling its coffers with bill issuance. But overall, so long as the Fed runs a floor system, a high ON RRP balance = lots of unused cash in the system, whereas a low balance suggests that cash has found alternative uses (and that any further liquidity tightening will start to pinch bank reserves). By early 2025, the tiny RRP balance implies we are near the point where liquidity is no longer excess – indeed, banks’ reserve balances (about $3.2 T in Feb 2025) are only now coming into focus as the next source of QT drainage.

Fed Influence vs. Market Plumbing: The developments in repo markets since 2019 raise an important question – has the Fed’s influence over broader liquidity and economic conditions weakened? In one sense, the Fed has shown enormous influence within money markets: its operations became the dominant factor in overnight rates. By 2022, private repo volumes were dwarfed by the Fed’s $2+ T RRP, and the Fed’s administered rates (IOER and RRP rate) effectively dictated short-term interest rates. However, this heavy-handed role can also be seen as a symptom of fragility or constraints in the system. The fact that an overnight funding crunch hit so suddenly in 2019 – and could only be quelled by Fed intervention – pointed to structural issues in liquidity distribution. Similarly, the Fed’s need to absorb trillions via RRP indicates that its massive QE liquidity did not fully transmigrate into real economy lending, but instead sat idle, requiring a Fed facility to stabilize the rate floor. As one veteran observer noted, the Fed’s “intrusive role” in intermediating short-term funds has side effects: it has encouraged markets to rely on the Fed rather than on private counterparties, potentially “undermining the efficiency and robustness” of the market-driven financial system. Moreover, once the buffer of excess liquidity is gone, the Fed’s influence is tested by more volatile market dynamics. Fed Chair Powell has insisted that QT should run quietly in the background of policy, but as excess liquidity evaporates, that claim is being tested. Analysts warn that if QT keeps going past the ON RRP buffer, every further dollar drained comes out of banks’ reserves, which could again tighten funding markets and force the Fed’s hand. Indeed, the memory of 2019’s spike – when reserves fell to ~$1.4 T and chaos ensued – looms large. Today’s reserves are still double that level, but if they approach “scarcity,” markets might preemptively react (higher repo/funding rates) well before an actual crisis. The Fed has tried to fortify its influence with new tools (such as a Standing Repo Facility to backstop repo rates at a ceiling), and these will likely mitigate sudden panics. Even so, the need for such tools underscores that the Fed’s control over liquidity is not absolute. It must carefully manage technical factors and “risk injecting uncertainty” into markets if it misjudges the ample-reserve boundary.

In broader economic terms, the Fed’s outsized liquidity injections and absorptions since 2019 had mixed real-world impact. Despite the Fed’s $4+ trillion QE during the pandemic, inflation remained quiescent until massive fiscal stimulus and supply shocks hit – suggesting that Fed liquidity on its own did not overheat the economy until other forces came into play. Then in 2022–23, even after aggressive rate hikes, the Fed saw inflation remain stubbornly above target, partly due to fiscal-driven demand and supply constraints. This has led some to argue that fiscal conditions and market structure are diluting the Fed’s influence on the real economy. For example, record Treasury issuance in 2023 pushed up long-term yields independent of Fed actions, complicating the Fed’s tightening path. The Fed is arguably more constrained now: it cannot blithely shrink its balance sheet without minding Treasury’s needs (debt management) or banking system thresholds, and it cannot easily ease policy without considering financial stability (after low rates contributed to bank asset/liability mismatches in 2023). All of this suggests that the Fed’s ability to steer broad conditions is now entangled with market plumbing and fiscal dynamics. As one analysis put it, the Fed has effectively become a “money market dealer of first resort” rather than a lender of last resort, which may leave it with less room for maneuver in influencing credit and economic outcomes in the traditional way. The upshot is a Fed whose day-to-day influence is immense in technical markets, but whose ultimate influence on the economy may be facing new limits and latencies.

Rethinking the Fed’s Future Role: Mandate, Tools, and Reforms

In light of these developments, many economists and policymakers have been reassessing the Federal Reserve’s mandate, structure, and toolkit. Two years of high inflation after 2021, coming on the heels of a decade of low inflation, underscored how challenging it is for the Fed to fulfill its statutory dual mandate (price stability and maximum employment) in a changing economy. Meanwhile, the Fed’s extraordinary actions (massive QE, direct credit backstops, etc.) and closer entanglement with fiscal authorities have prompted calls for reform. Below, we critically examine several major areas of debate – from the efficacy of the dual mandate itself to proposals for new policy frameworks – all through a lens of lessons learned and the Fed’s sometimes diminished effectiveness in recent years.

1. Re-evaluating the Dual Mandate’s Effectiveness: The Fed’s dual mandate – enshrined as low inflation and maximum sustainable employment – has guided policy for decades. Critics now argue that the Fed’s interpretation of this mandate contributed to policy mistakes in the 2020s. In its 2019–2020 strategy review, the Fed adopted a “flexible average inflation targeting” (FAIT) approach that put greater weight on the employment leg of the mandate. Specifically, the Fed vowed not to raise rates preemptively based on low unemployment alone, and to allow inflation to run “moderately above 2%” following periods of undershooting – essentially a one-sided makeup strategy. In practice, this meant the FOMC in 2021 was deliberately slow to tighten policy even as inflation accelerated, because the labor market had not yet reached “maximum employment” by their assessments. **Economists Gauti Eggertsson and Don Kohn find that these FAIT changes (focusing on “shortfalls” in employment and seeking inflation overshoots) effectively “put greater emphasis on the maximum employment part of the dual mandate” and introduced an inflationary bias. Indeed, former Fed officials Mickey Levy and Charles Plosser noted that under FAIT the Fed eliminated “preemptive” rate hikes – it would no longer respond to looming inflation based on job market signals alone. This framework, while well-intended to avoid under-shooting inflation, arguably left the Fed “behind the curve” when pandemic-era inflation surged well above 2%.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself conceded that tying liftoff to both full employment and 2% inflation was a mistake in hindsight: “I don’t think I would do that again,” Powell said of the dual thresholds for rate hikes. The forward guidance in 2020–21 committed to no rate increases until the dual mandate was fully met – a condition that, as it turned out, delayed action even as prices soared. The result was the worst inflation in 40 years and, ironically, a later overshoot of the employment goal (the job market became extremely tight with deeply negative real rates). This episode has intensified debate over whether the dual mandate is too internally conflicting or imprecise for modern policy. One proposal is to refocus or clarify the mandate: for example, some suggest prioritizing price stability more explicitly. (The European Central Bank, by contrast, has a primary price stability mandate and considers employment secondary.) Others argue the Fed’s mandate should be expanded to include financial stability as an explicit goal, given that low inflation and low unemployment alone don’t guarantee stability. A Boston Fed study even asks if the U.S. should have a “ternary mandate” that factors in financial stability risks when setting rates.

Another forward-looking idea that has gained traction is to adopt a single metric that inherently balances inflation and growth – namely Nominal GDP targeting (addressed more later). Proponents like the Mercatus Center’s David Beckworth contend that a nominal GDP level target would “offer the Fed a more reliable path toward achieving its dual mandate”, effectively merging the goals into one. By targeting the total dollar value of output (which grows with inflation + real growth), the Fed would implicitly stabilize both prices and employment over the medium run. This approach could reduce the ambiguity the Fed faces in weighting two objectives. Indeed, research shows that had the Fed been following a nominal GDP path target in 2021, it would have raised rates sooner (responding to booming demand) and perhaps mitigated the inflation overshoot. In summary, while the dual mandate remains law, there is a palpable push to reformulate the Fed’s objectives – either through new legislation or through frameworks like NGDP targeting or symmetric level targets – so that the Fed is less prone to the kind of trade-off miscalculations that occurred in 2021–22.

2. Fed–Treasury Coordination and “Fiscal Dominance” Concerns: Another area under scrutiny is the relationship between the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury. The crisis responses of 2008 and 2020 saw an unprecedented blurring of lines – the Fed bought trillions in Treasuries and even corporate bonds, essentially backstopping fiscal stimulus with monetary expansion. While the Fed insists its independence remains intact, critics worry that the U.S. may be drifting into fiscal dominance, where Fed policy is subservient to financing government debt. One red flag: the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs or QE) have coincided with huge federal deficits, which “bear a strong resemblance to monetary financing of the deficit,” as one report bluntly noted. During the pandemic, the Fed absorbed so much Treasury issuance that it kept the government’s borrowing costs artificially low despite record spending – an arguably necessary move in a crisis, but one that creates political expectations for easy financing.

As the Fed now unwinds its balance sheet, tensions with Treasury’s goals are emerging. The Fed’s QT (letting bonds mature) forces Treasury to issue equivalent new debt to the public, which influences interest rates and liquidity – effectively Treasury’s decisions about debt management can complicate the Fed’s tightening. For instance, in mid-2023, when the Treasury announced a big increase in long-term bond issuance, 10-year yields spiked, tightening financial conditions faster than Fed policy alone. Conversely, Treasury’s heavy bill issuance post-debt-ceiling helped drain the ON RRP facility (as noted), acting as a de-facto tightening that the Fed welcomed. Such interactions show that the Fed and Treasury are engaged in a delicate dance, albeit informally.

Experts are calling for clearer Fed-Treasury coordination – or separation. One school of thought emphasizes re-establishing boundaries: the Fed should avoid credit allocation decisions that encroach on fiscal policy. For example, purchasing trillions in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) during QE has been criticized as the Fed favoring housing finance – a “historic policy mistake” when continued into 2021–22 despite an already hot housing market. Because buying MBS or specific corporate bonds effectively picks winners and losers, many argue the Fed went beyond monetary policy into the fiscal realm of credit allocation. To preserve long-run independence, some suggest Congress should limit the Fed’s asset purchase authority – e.g. restricting purchases to Treasury securities (and perhaps only shorter maturities) except in emergencies. The idea is that decisions like subsidizing mortgages or municipal bonds should be made by elected officials via fiscal channels, not unelected central bankers.

On the other hand, some argue for better coordination mechanisms for when monetary and fiscal policies inevitably intersect. One proposal is more systematic communication on debt management: e.g. the Treasury could structure its issuance (bills vs bonds) in a way that supports the Fed’s monetary stance (this hearkens back to the spirit of the 1951 Treasury-Fed Accord, which freed the Fed from fixing yields for Treasury). Today, that might mean Treasury keeping more debt in short-term bills when the Fed is raising rates – to ensure abundant safe assets for MMFs and reduce reliance on the Fed’s RRP. Conversely, in crises, formalized Treasury backstops for Fed emergency programs (as used in 2020 via the CARES Act funds) can help align fiscal risk-taking with the Fed’s lending. The underlying principle is to avoid situations where the Fed feels compelled to accommodate fiscal needs at the expense of its mandate. With U.S. debt above 100% of GDP and rising interest costs, the risk of fiscal dominance is not just academic. Mohamed El-Erian and others have warned that if the government’s debt trajectory remains unsustainable, the Fed could face pressure to tolerate higher inflation or cap interest rates (to prevent a debt crisis). This would be a regime where, effectively, “the Fed’s tools aren’t made for fiscal dominance” – i.e. monetary policy would lose credibility as it bends to fiscal imperatives.

In a forward-looking sense, addressing Fed-Treasury coordination may involve difficult choices. Some have mooted raising the inflation target (say to 3%) to ease the burden of debt reduction – though this is controversial and amounts to sanctioned fiscal dominance by inflation. Others suggest that in the next downturn, rather than relying solely on Fed QE, the Treasury and Congress should take the lead with fiscal expansion (financed by debt that the Fed might temporarily help absorb) – a policy mix known as fiscal-monetary coordination or even “helicopter money” in extreme form. But this would require an explicit framework to preserve the Fed’s independence once normal times return. Without such a framework, the concern is that the Fed’s credibility on inflation could be eroded by perceptions it will always rescue the Treasury (the classic “bond vigilante” fear). In sum, the post-2020 world has laid bare that the Fed’s and Treasury’s decisions are tightly linked. Strengthening that relationship in a transparent, rules-based way – or legally delimiting it – is seen as vital to ensure that high government debt doesn’t end up “overpowering the central bank’s ability to manage inflation.”

3. Communication Strategy and Data Dependence: The Fed’s communication practices, including forward guidance and its “data-dependent” approach, are under the microscope after the volatile outcomes of recent years. In the 2010s, the Fed increasingly used forward guidance to shape market expectations (for example, signaling rates would stay near zero far into the future). This tool arguably backfired in the pandemic recovery. The FOMC’s guidance in late 2020 promised zero rates until maximum employment was achieved, and inflation was on track to exceed 2% – a stance that was “poorly designed” for the scenario that unfolded. Inflation ripped higher faster than expected, but the Fed’s guidance had tied its hands, leading to a long delay in liftoff. As noted, the FOMC was hesitant to activate an “escape clause” despite obvious upside risks to price stability. Critics say this illustrates a flaw in overly rigid forward guidance: it can undermine policy flexibility when unprecedented shocks hit. Moving forward, many suggest the Fed should simplify its guidance and emphasize uncertainty. Powell’s communications in 2023–24 did shift in this direction – repeatedly stressing that the Fed is “data-dependent” and not on a preset course, essentially walking back the calendar-based or criteria-based commitments of earlier years.

However, “data dependence” has its critics as well. Some argue it makes the Fed reactive and potentially “behind the curve”, as it was in 2021. By waiting for realized data (like several months of realized inflation) before reacting, the Fed can be late in tightening or easing. Economists advocate that the Fed incorporate more forward-looking rules or indicators in its communications. For instance, a nominal GDP forecast, or market-based inflation expectations, could be referenced as guideposts for policy decisions – giving the public a sense of a rule-like behavior without binding the Fed to a single metric. Indeed, proponents of rules-based policy (like a Taylor Rule) believe the Fed’s discretionary, judgment-based approach in recent years led to avoidable errors. They point out that simple policy rules had indicated a need to start raising rates by early 2021, whereas the Fed’s subjective assessment (focused on labor market shortfalls and “transitory” inflation hopes) kept policy too easy. The Fed itself has listed reasons it resists strict policy rules – e.g. that simple rules “abstract from many factors” and aren’t well-suited when neutral rates or full employment levels are uncertain. But reformers at places like the Cato Institute counter that those critiques are “invalid” or at least overblown, arguing that robust rules can perform well, and that the Fed’s discretion has costs. Legislation has even been proposed in Congress (in past years) to require the Fed to report how its policies compare to a reference rule (the “Taylor Rule Accountability Act”), aiming to prod the Fed toward a more systematic strategy.

Moving forward, we are likely to see the Fed refine its communication to regain credibility. Powell has already improved transparency about the Fed’s reaction function by explicitly saying, for example, that previous forward guidance tying rate hikes to dual-mandate outcomes was a mistake. The Fed’s 2024–25 framework review will likely address how it communicates policy paths. A plausible outcome is that the Fed will eschew hard triggers in guidance (as used in 2020) and instead use qualitative guidance that retains flexibility (“if we see X trend, we expect to….”). The Fed might also place less emphasis on its “dot plot” of future rate projections, since those were taken as commitments but proved very wrong during the pandemic recovery. Data dependence, in the sense of humility and conditionality, is generally positive – but the Fed must clarify that being data-dependent doesn’t mean being backward-looking. One suggestion is for the Fed to communicate more about forecasts and probabilities: for example, explicitly saying “if our inflation forecast one year out remains above target, we will move faster,” etc. This could align public expectations more with the Fed’s intentions under various data outcomes, rather than having markets constantly second-guess how each new data point will sway the Fed. Ultimately, improving communication and decision-making transparency is seen as key to avoiding the kind of surprise pivot that happened in 2022, when the Fed had to abruptly shift from dovish guidance to rapid hikes, jolting markets and arguably exacerbating volatility.

4. Structural and Governance Reforms: Accountability, Mandates, and Limits to QE: Beyond policy strategy tweaks, there are also institutional reform ideas aimed at the Fed. Some critics argue that the Fed has accumulated too much power without adequate accountability, especially after the 2008 crisis expanded its role. A report from the Manhattan Institute points out that the Fed’s mandate has “expanded to include inherently political activities” like credit allocation and regulatory activism (e.g. climate risk initiatives). At the same time, the Fed’s leadership has become more entwined with politics (many top officials cycling in from political roles), and yet there is little consequence for policy errors. For instance, Fed officials faced no penalty for misjudging inflation in 2021–22, even though that lapse had severe economic costs, whereas they did face pressure to resign over unrelated ethics issues. This imbalance, reform proponents say, indicates a need to increase Fed accountability without undermining its operational independence.

One bold proposal is to overhaul the Fed’s governance structure to inject more democratic oversight. For example, shortening the tenure of Fed Governors and making them explicitly subject to reappointment by the President (or even allowing the President to remove them) has been suggested to ensure the Fed doesn’t drift too far from its mandate. Such a change would tilt independence towards accountability, though skeptics fear it could also politicize monetary policy. To counter that, the same proposal recommends empowering the regional Federal Reserve Banks (whose presidents are not political appointees) – for instance, having their boards (which currently include bankers and businesspeople) instead be chosen by state governors to broaden representation. The idea is a “balanced” governance model: more White House oversight of the Washington-based Board (for legitimacy), combined with a stronger voice for regional Fed presidents (to decentralize power). While these specific reforms are debated, they highlight a core issue: the Fed’s credibility relies on both expertise and public trust, and the latter can erode if the Fed is seen as unaccountable or straying into politics. By refocusing the Fed on a narrower mandate – e.g. instructing it to stick to macroeconomic stabilization and not social or credit policies – and establishing clearer consequences or review for major policy deviations, reformers believe the Fed will deliver better outcomes.

Another structural reform area is imposing limits on the Fed’s emergency powers and balance sheet. During crises, the Fed has stretched its emergency lending authority to backstop everything from commercial paper to municipal bonds (often in cooperation with Treasury). Some in Congress have already tightened the rules (requiring Treasury sign-off for broad programs, as in 2020). Further limits could include: prohibiting the Fed from buying certain asset classes (to prevent “mission creep”), capping the size of QE programs unless inflation is below a certain level, or requiring a sunset strategy for QE (so the Fed can’t hold huge assets indefinitely without justification). Indeed, the Fed’s large balance sheet has fiscal implications – in 2022 the Fed began remitting zero profits to Treasury and instead incurred operating losses (due to higher interest paid on reserves/RRPs than it earns on its bond portfolio). This means taxpayers effectively foot the bill for the Fed’s past QE via reduced Fed remittances. While not catastrophic, it has politicized QE by highlighting that it can cost the government money in a tightening cycle. Hence, a possible reform is to require the Fed to evaluate the financial impacts of its asset purchases on a rolling basis and perhaps maintain capital against losses (currently Fed losses are swept under the rug as a deferred asset). Ideas like these aim to rein in an ever-expanding Fed balance sheet and ensure it’s used only when truly needed for macro stabilization, not as a routine tool or to facilitate fiscal borrowing.

5. Alternative Policy Frameworks – NGDP Targeting and Price-Level Targeting: As mentioned, alternatives to the current flexible inflation targeting regime are gaining interest. Nominal GDP level targeting (NGDPLT) is one such framework. Advocates argue it could address several flaws in the current approach: it automatically accommodates supply shocks (if real growth falls, NGDP targeting allows inflation to rise somewhat, avoiding an overly tight policy) and it provides a single clear target for accountability. NGDPLT would effectively unify the dual mandate by aiming for a stable path of nominal economic size. It also inherently includes a “make-up” mechanism: if nominal GDP falls below trend (say due to a recession), the Fed commits to restoring it to the pre-determined path, which might mean temporarily higher inflation – but importantly, it distinguishes demand from supply. The Mercatus Center paper on the Fed’s 2024 review makes the case that NGDP targeting would have prevented the Fed from overstimulating in 2020–21, because nominal GDP growth was far above target by late 2021 even though inflation and employment targets were considered separately. Under an NGDP level target, the Fed would have tightened sooner and more gradually, potentially avoiding the need for very rapid hikes later. Of course, adopting NGDPLT would be a major regime change – the Fed would need to retrain the public and markets to pay attention to nominal GDP reports, and it would need to manage transitional challenges (what is the starting “level”, how to communicate temporary overshoots, etc.). Nonetheless, the fact that mainstream economists and even some Fed officials are discussing it indicates openness to big ideas in how we guide monetary policy.

Another framework is price-level targeting (PLT), which is like inflation targeting with memory: the central bank targets a specific path for the price index (e.g. 2% growth per year on average). Under PLT, if inflation undershoots one year, the bank must overshoot the next to get the price level back on track (and vice versa). A key benefit is that it firmly anchors long-run expectations – people know that any deviation will be corrected, so the price level 5, 10 years out should be predictable. This can help prevent the kind of drift that occurred in the 2010s when inflation persistently undershot 2% (leading to doubts about the Fed’s ability to reach its target). Several prominent Fed thinkers (including former Chair Ben Bernanke and NY Fed President John Williams) have expressed support for variants of price-level targeting, especially as a tool to combat the zero bound problem. Under PLT, if a recession pushes inflation below target for a time, everyone knows the Fed will later allow catch-up inflation above 2%. That expectation of future easier policy can stimulate demand during the recession (by lowering expected real interest rates even if current rates are at zero). In other words, PLT shifts expectations in a recessionary environment in a way that pure inflation targeting cannot, potentially avoiding deflationary spirals. This is why PLT is seen as a remedy for deflationary recessions and the zero-lower-bound trap.

The Fed in 2020 stopped short of full price-level targeting, opting instead for the softer “average inflation targeting” (which implies some makeup for past undershoots but is less formulaic). The experience of the past two years – where the Fed did allow an overshoot but then had to rein it in – might make PLT politically hard to swallow for now. Critics of PLT point out its potential downside: if faced with a large overshoot (as in 2021–22), strict price-level targeting would force the Fed to create a recession (and undershoot inflation later) to return the price level to path, which could be very painful. In effect, PLT trades some flexibility for credibility. A compromise could be something like Bernanke’s suggestion: use price-level targeting only during ZLB episodes (to guide expectations out of a deflationary trap), then revert to inflation targeting once away from the zero bound. This “temporary PLT” approach was discussed by the Fed in 2019 but not adopted; it may get a second look in the next framework review.